A significant percentage of modern, interactive websites allow some form of user interaction – from allowing simple comments on a blog, to full editorial control of articles on a news site. If a site offers any sort of eCommerce, authentication and authorization of paying customers is essential.

Just managing users – lost usernames, forgotten passwords and keeping information up to date – can be a real pain. As a programmer, writing an authentication system can be even worse.

Lucky for us, Django comes with a user authentication system installed automatically for your convenience when your ran django-admin startproject.

Django provides a default implementation for managing user accounts, groups, permissions and cookie-based user sessions out of the box.

Like most things in Django, the default implementation is fully extendible and customizable to suit your project’s needs. So let’s jump right in.

- Authentication in Web requests

- How to log a user in

- How to log a user out

- Limiting access to logged-in users

Overview

The Django authentication system handles both authentication and authorization. Briefly, authentication verifies a user is who they claim to be, and authorization determines what an authenticated user is allowed to do. Here the term authentication is used to refer to both tasks.

The auth system consists of:

- Users

- Permissions: Binary (yes/no) flags designating whether a user may perform a certain task

- Groups: A generic way of applying labels and permissions to more than one user

- A configurable password hashing system

- Forms and view tools for logging in users, or restricting content

- A pluggable backend system

The authentication system in Django aims to be very generic and doesn’t provide some features commonly found in web authentication systems. Solutions for some of these common problems have been implemented in third-party packages:

- Password strength checking

- Throttling of login attempts

- Authentication against third-parties (OAuth, for example)

Using the Django authentication system

Django’s authentication system in its default configuration has evolved to serve the most common project needs, handling a reasonably wide range of tasks, and has a careful implementation of passwords and permissions. For projects where authentication needs differ from the default, Django also supports extensive extension and customization of authentication.

User objects

User objects are the core of the authentication system. They typically represent the people interacting with your site and are used to enable things like restricting access, registering user profiles, associating content with creators etc. Only one class of user exists in Django’s authentication framework, i.e.,"superusers" or admin "staff" users are just user objects with special attributes set, not different classes of user objects.

The primary attributes of the default user are:

usernamepasswordemailfirst_namelast_name

Creating users

The simplest, and least error prone way to create and manage users is through the Django admin. Django also provides built in views and forms to allow users to log in and out and change their own password.

We will be looking at user management via the admin and generic user forms a bit later in this chapter, but first, lets look at how we would handle user authentication directly.

The most direct way to create users is to use the included create_user() helper function:

>>> from django.contrib.auth.models import User

>>> user = User.objects.create_user("john", "lennon@thebeatles.com", "johnpassword")

# At this point, user is a User object that has already been saved

# to the database. You can continue to change its attributes

# if you want to change other fields.

>>> user.last_name = "Lennon"

>>> user.save()

Creating superusers

Create superusers using the createsuperuser command:

$ python manage.py createsuperuser --username=joe --email=joe@example.com

You will be prompted for a password. After you enter one, the user will be created immediately. If you leave off the --username or the --email options, it will prompt you for those values.

Changing passwords

Django does not store raw (clear text) passwords on the user model, but only a hash. Because of this, do not attempt to manipulate the password attribute of the user directly. This is why a helper function is used when creating a user.

To change a user’s password, you have two options:

manage.py changepassword *username* <changepassword> offers a method of changing a User’s password from the command line. It prompts you to change the password of a given user which you must enter twice. If they both match, the new password will be changed immediately. If you do not supply a user, the command will attempt to change the password of the user whose username matches the current system user.

You can also change a password programmatically, using set_password():

>>> from django.contrib.auth.models import User

>>> u = User.objects.get(username="john")

>>> u.set_password("new password")

>>> u.save()

Changing a user’s password will log out all their sessions if the SessionAuthenticationMiddleware is enabled.

Authenticating Users

authenticate(**credentials)

To authenticate a given username and password, use authenticate(). It takes credentials in the form of keyword arguments, for the default configuration this is username and password, and it returns a User object if the password is valid for the given username. If the password is invalid, authenticate() returns None. Example:

from django.contrib.auth import authenticate

user = authenticate(username="john", password="secret")

if user is not None:

# the password verified for the user

if user.is_active:

print("User is valid, active and authenticated")

else:

print("The password is valid, but the account has been disabled!")

else:

# the authentication system was unable to verify the username and password

print("The username and password were incorrect.")

Note

This is a low level way to authenticate a set of credentials; for example, it’s used by theRemoteUserMiddleware. Unless you are writing your own authentication system, you probably won’t use this. Rather if you are looking for a way to limit access to logged in users, see the login_required() decorator.

Permissions and Authorization

Django comes with a simple permissions system. It provides a way to assign permissions to specific users and groups of users.

It’s used by the Django admin site, but you’re welcome to use it in your own code.

The Django admin site uses permissions as follows:

- Access to view the “add” form and add an object is limited to users with the “add” permission for that type of object

- Access to view the change list, view the “change” form and change an object is limited to users with the “change” permission for that type of object

- Access to delete an object is limited to users with the “delete” permission for that type of object

Permissions can be set not only per type of object, but also per specific object instance. By using thehas_add_permission(), has_change_permission() and has_delete_permission() methods provided by theModelAdmin class, it is possible to customize permissions for different object instances of the same type.

User objects have two many-to-many fields: groups and user_permissions. User objects can access their related objects in the same way as any other Django model.

Default permissions

When django.contrib.auth is listed in your INSTALLED_APPS setting, it will ensure that three default permissions – add, change and delete – are created for each Django model defined in one of your installed applications.

These permissions will be created when you run manage.py migrate the first time you run migrate after adding django.contrib.auth to INSTALLED_APPS, the default permissions will be created for all previously-installed models, as well as for any new models being installed at that time. Afterward, it will create default permissions for new models each time you run manage.py migrate.

Assuming you have an application with an app_label foo and a model named Bar, to test for basic permissions you should use:

- add:

user.has_perm("foo.add_bar") - change:

user.has_perm("foo.change_bar") - delete:

user.has_perm("foo.delete_bar")

The Permission model is rarely accessed directly.

Groups

django.contrib.auth.models.Group models are a generic way of categorizing users so you can apply permissions, or some other label, to those users. A user can belong to any number of groups.

A user in a group automatically has the permissions granted to that group. For example, if the group Site editors has the permission can_edit_home_page, any user in that group will have that permission.

Beyond permissions, groups are a convenient way to categorize users to give them some label, or extended functionality. For example, you could create a group "Special users", and you could write code that could, say, give them access to a members-only portion of your site, or send them members-only email messages.

Programmatically creating permissions

While custom permissions can be defined within a model’s Meta class, you can also create permissions directly. For example, you can create the can_publish permission for a BookReview model in books:

from books.models import BookReview

from django.contrib.auth.models import Group, Permission

from django.contrib.contenttypes.models import ContentType

content_type = ContentType.objects.get_for_model(BookReview)

permission = Permission.objects.create(codename="can_publish",

name="Can Publish Reviews",

content_type=content_type)

The permission can then be assigned to a User via its user_permissions attribute or to a Group via itspermissions attribute.

Permission caching

The ModelBackend caches permissions on the User object after the first time they need to be fetched for a permissions check. This is typically fine for the request-response cycle since permissions are not typically checked immediately after they are added (in the admin, for example). If you are adding permissions and checking them immediately afterward, in a test or view for example, the easiest solution is to re-fetch theUser from the database. For example:

from django.contrib.auth.models import Permission, User

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404

def user_gains_perms(request, user_id):

user = get_object_or_404(User, pk=user_id)

# any permission check will cache the current set of permissions

user.has_perm("books.change_bar")

permission = Permission.objects.get(codename="change_bar")

user.user_permissions.add(permission)

# Checking the cached permission set

user.has_perm("books.change_bar") # False

# Request new instance of User

user = get_object_or_404(User, pk=user_id)

# Permission cache is repopulated from the database

user.has_perm("books.change_bar") # True

...

Authentication in Web requests

Django uses sessions and middleware to hook the authentication system into request objects.

These provide a request.user attribute on every request which represents the current user. If the current user has not logged in, this attribute will be set to an instance of AnonymousUser, otherwise it will be an instance of User.

You can tell them apart with is_authenticated(), like so:

if request.user.is_authenticated():

# Do something for authenticated users.

else:

# Do something for anonymous users.

How to log a user in

If you have an authenticated user you want to attach to the current session – this is done with a login()function.

login()

To log a user in, from a view, use login(). It takes an HttpRequest object and a User object. login() saves the user’s ID in the session, using Django’s session framework.

Note that any data set during the anonymous session is retained in the session after a user logs in.

This example shows how you might use both authenticate() and login():

from django.contrib.auth import authenticate, login

def my_view(request):

username = request.POST["username"]

password = request.POST["password"]

user = authenticate(username=username, password=password)

if user is not None:

if user.is_active:

login(request, user)

# Redirect to a success page.

else:

# Return a "disabled account" error message

else:

# Return an "invalid login" error message.

Calling authenticate() first

When you’re manually logging a user in, you must call authenticate() before you call login(). authenticate()sets an attribute on the User noting which authentication backend successfully authenticated that user, and this information is needed later during the login process. An error will be raised if you try to login a user object retrieved from the database directly.

How to log a user out

logout()

To log out a user who has been logged in via django.contrib.auth.login(), use django.contrib.auth.logout()within your view. It takes an HttpRequest object and has no return value. Example:

from django.contrib.auth import logout

def logout_view(request):

logout(request)

# Redirect to a success page.

Note that logout() doesn’t throw any errors if the user wasn’t logged in.

When you call logout(), the session data for the current request is completely cleaned out. All existing data is removed. This is to prevent another person from using the same Web browser to log in and have access to the previous user’s session data. If you want to put anything into the session that will be available to the user immediately after logging out, do that after calling django.contrib.auth.logout().

Limiting access to logged-in users

THE RAW WAY

The simple, raw way to limit access to pages is to check request.user.is_authenticated() and either redirect to a login page:

from django.shortcuts import redirect

def my_view(request):

if not request.user.is_authenticated():

return redirect("/login/?next=%s" % request.path)

# ...

…or display an error message:

from django.shortcuts import render

def my_view(request):

if not request.user.is_authenticated():

return render(request, "books/login_error.html")

# ...

THE LOGIN_REQUIRED DECORATOR

django.contrib.auth.decorators.login_required([*redirect_field_name=REDIRECT_FIELD_NAME*,*login_url=None*])

As a shortcut, you can use the convenient login_required() decorator:

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required

@login_required

def my_view(request):

...

login_required() does the following:

- If the user isn’t logged in, redirect to

LOGIN_URL, passing the current absolute path in the query string. Example:/accounts/login/?next=/reviews/3/. - If the user is logged in, execute the view normally. The view code is free to assume the user is logged in.

By default, the path that the user should be redirected to upon successful authentication is stored in a query string parameter called "next". If you would prefer to use a different name for this parameter,login_required() takes an optional redirect_field_name parameter:

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required

@login_required(redirect_field_name="my_redirect_field")

def my_view(request):

...

Note that if you provide a value to redirect_field_name, you will most likely need to customize your login template as well, since the template context variable which stores the redirect path will use the value ofredirect_field_name as its key rather than "next" (the default).

login_required() also takes an optional login_url parameter. Example:

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required

@login_required(login_url="/accounts/login/")

def my_view(request):

...

Note that if you don’t specify the login_url parameter, you’ll need to ensure that the LOGIN_URL and your login view are properly associated. For example, using the defaults, add the following lines to your URLconf:

from django.contrib.auth import views as auth_views

url(r"^accounts/login/$", auth_views.login),

The LOGIN_URL also accepts view function names and named URL patterns. This allows you to freely remap your login view within your URLconf without having to update the setting.

Note

The login_required decorator does NOT check the is_active flag on a user.

LIMITING ACCESS TO LOGGED-IN USERS THAT PASS A TEST

To limit access based on certain permissions or some other test, you’d do essentially the same thing as described in the previous section.

The simple way is to run your test on request.user in the view directly. For example, this view checks to make sure the user has an email in the desired domain:

def my_view(request):

if not request.user.email.endswith("@example.com"):

return HttpResponse("You can"t leave a review for this book.")

# ...

django.contrib.auth.decorators.user_passes_test(func[, *login_url=None*,*redirect_field_name=REDIRECT_FIELD_NAME*])

As a shortcut, you can use the convenient user_passes_test decorator:

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import user_passes_test

def email_check(user):

return user.email.endswith("@example.com")

@user_passes_test(email_check)

def my_view(request):

...

user_passes_test() takes a required argument: a callable that takes a User object and returns True if the user is allowed to view the page. Note that user_passes_test() does not automatically check that the User is not anonymous.

user_passes_test() takes two optional arguments:

login_urlLets you specify the URL that users who don’t pass the test will be redirected to. It may be a login page and defaults to LOGIN_URL` if you don’t specify one.redirect_field_nameSame as forlogin_required(). Setting it toNoneremoves it from the URL, which you may want to do if you are redirecting users that don’t pass the test to a non-login page where there’s no “next page”.

For example:

@user_passes_test(email_check, login_url="/login/")

def my_view(request):

...

THE PERMISSION_REQUIRED DECORATOR

django.contrib.auth.decorators.permission_required(perm[, *login_url=None*, *raise_exception=False*])

It’s a relatively common task to check whether a user has a particular permission. For that reason, Django provides a shortcut for that case: the permission_required() decorator.:

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import permission_required

@permission_required("reviews.can_vote")

def my_view(request):

...

Just like the has_perm() method, permission names take the form "<app label>.<permission codename>" (i.e.reviews.can_vote for a permission on a model in the reviews application).

The decorator may also take a list of permissions.

Note that permission_required() also takes an optional login_url parameter. Example:

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import permission_required

@permission_required("reviews.can_vote", login_url="/loginpage/")

def my_view(request):

...

As in the login_required() decorator, login_url defaults to LOGIN_URL`.

If the raise_exception parameter is given, the decorator will raise PermissionDenied, prompting the 403 (HTTP Forbidden) view instead of redirecting to the login page.

APPLYING PERMISSIONS TO GENERIC VIEWS

To apply a permission to a class-based generic view , decorate the View.dispatch method on the class. Another approach is to write a mixin that wraps as_view().

SESSION INVALIDATION ON PASSWORD CHANGE

If your AUTH_USER_MODEL inherits from AbstractBaseUser or implements its own get_session_auth_hash()method, authenticated sessions will include the hash returned by this function. In the AbstractBaseUsercase, this is an HMAC of the password field. If the SessionAuthenticationMiddleware is enabled, Django verifies that the hash sent along with each request matches the one that’s computed server-side. This allows a user to log out all of their sessions by changing their password.

The default password change views included with Django, django.contrib.auth.views.password_change() and the user_change_password view in the django.contrib.auth admin, update the session with the new password hash so that a user changing their own password won’t log themselves out. If you have a custom password change view and wish to have similar behavior, use this function:

django.contrib.auth.decorators.update_session_auth_hash(request, user)

This function takes the current request and the updated user object from which the new session hash will be derived and updates the session hash appropriately. Example usage:

from django.contrib.auth import update_session_auth_hash

def password_change(request):

if request.method == "POST":

form = PasswordChangeForm(user=request.user, data=request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

form.save()

update_session_auth_hash(request, form.user)

else:

...

Note

Since get_session_auth_hash() is based on SECRET_KEY, updating your site to use a new secret will invalidate all existing sessions.

Authentication Views

Django provides several views that you can use for handling login, logout, and password management. These make use of the built-in auth forms but you can pass in your own forms as well.

Django provides no default template for the authentication views – however the template context is documented for each view below.

The built-in views all return a TemplateResponse instance, which allows you to easily customize the response data before rendering. Most built-in authentication views provide a URL name for easier reference.

login

django.contrib.auth.views.login(request[, *template_name*, *redirect_field_name*, *authentication_form*,*current_app*, *extra_context*])

Logs a user in.

Default URL: /login/

Optional arguments:

template_name: The name of a template to display for the view used to log the user in. Defaults toregistration/login.html.redirect_field_name: The name of aGETfield containing the URL to redirect to after login. Defaults tonext.authentication_form: A callable (typically just a form class) to use for authentication. Defaults toAuthenticationForm.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

Here’s what django.contrib.auth.views.login does:

- If called via

GET, it displays a login form that POSTs to the same URL. More on this in a bit. - If called via

POSTwith user submitted credentials, it tries to log the user in. If login is successful, the view redirects to the URL specified innext. Ifnextisn’t provided, it redirects toLOGIN_REDIRECT_URL(which defaults to/accounts/profile/). If login isn’t successful, it redisplays the login form.

It’s your responsibility to provide the html for the login template , called registration/login.html by default. This template gets passed four template context variables:

form: AFormobject representing theAuthenticationForm.next: The URL to redirect to after successful login. This may contain a query string, too.site: The currentSite, according to theSITE_IDsetting. If you don’t have the site framework installed, this will be set to an instance ofRequestSite, which derives the site name and domain from the currentHttpRequest.site_name: An alias forsite.name. If you don’t have the site framework installed, this will be set to the value ofrequest.META["SERVER_NAME"].

If you’d prefer not to call the template registration/login.html, you can pass the template_name parameter via the extra arguments to the view in your URLconf. For example, this URLconf line would usebooks/login.html instead:

url(r"^accounts/login/$", auth_views.login, {"template_name": "books/login.html"}),

You can also specify the name of the GET field which contains the URL to redirect to after login by passingredirect_field_name to the view. By default, the field is called next.

Here’s a sample registration/login.html template you can use as a starting point. It assumes you have abase.html template that defines a content block:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

{% if form.errors %}

<p>Your username and password didn"t match. Please try again.</p>

{% endif %}

<form method="post" action="{% url "django.contrib.auth.views.login" %}">

{% csrf_token %}

<table>

<tr>

<td>{{ form.username.label_tag }}</td>

<td>{{ form.username }}</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>{{ form.password.label_tag }}</td>

<td>{{ form.password }}</td>

</tr>

</table>

<input type="submit" value="login" />

<input type="hidden" name="next" value="{{ next }}" />

</form>

{% endblock %}

If you have customized authentication you can pass a custom authentication form to the login view via theauthentication_form parameter. This form must accept a request keyword argument in its __init__ method, and provide a get_user method which returns the authenticated user object (this method is only ever called after successful form validation).

logout

django.contrib.auth.views.logout(request[, *next_page*, *template_name*, *redirect_field_name*, *current_app*,*extra_context*])

Logs a user out.

Default URL: /logout/

Optional arguments:

next_page: The URL to redirect to after logout.template_name: The full name of a template to display after logging the user out. Defaults toregistration/logged_out.htmlif no argument is supplied.redirect_field_name: The name of aGETfield containing the URL to redirect to after log out. Defaults tonext. Overrides thenext_pageURL if the givenGETparameter is passed.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

Template context:

title: The string “Logged out”, localized.site: The currentSite, according to theSITE_IDsetting. If you don’t have the site framework installed, this will be set to an instance ofRequestSite, which derives the site name and domain from the currentHttpRequest.site_name: An alias forsite.name. If you don’t have the site framework installed, this will be set to the value ofrequest.META["SERVER_NAME"].current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

logout_then_login

django.contrib.auth.views.logout_then_login(request[, *login_url*, *current_app*, *extra_context*])

Logs a user out, then redirects to the login page.

Default URL: None provided.

Optional arguments:

login_url: The URL of the login page to redirect to. Defaults toLOGIN_URLif not supplied.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

password_change

django.contrib.auth.views.password_change(request[, *template_name*, *post_change_redirect*,*password_change_form*, *current_app*, *extra_context*])

Allows a user to change their password.

Default URL: /password_change/

Optional arguments:

template_name: The full name of a template to use for displaying the password change form. Defaults toregistration/password_change_form.htmlif not supplied.post_change_redirect: The URL to redirect to after a successful password change.password_change_form: A custom “change password” form which must accept auserkeyword argument. The form is responsible for actually changing the user’s password. Defaults toPasswordChangeForm.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

Template context:

form: The password change form (seepassword_change_formabove).

password_change_done

django.contrib.auth.views.password_change_done(request[, *template_name*, *current_app*, *extra_context*])

The page shown after a user has changed their password.

Default URL: /password_change_done/

Optional arguments:

template_name: The full name of a template to use. Defaults toregistration/password_change_done.htmlif not supplied.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

password_reset

django.contrib.auth.views.password_reset(request[, *template_name*, *email_template_name*,*password_reset_form*, *token_generator*, *post_reset_redirect*, *from_email*, *current_app*, *extra_context*,*html_email_template_name*])

Allows a user to reset their password by generating a one-time use link that can be used to reset the password, and sending that link to the user’s registered email address.

If the email address provided does not exist in the system, this view won’t send an email, but the user won’t receive any error message either. This prevents information leaking to potential attackers. If you want to provide an error message in this case, you can subclass PasswordResetForm and use thepassword_reset_form argument.

Users flagged with an unusable password (see set_unusable_password() aren’t allowed to request a password reset to prevent misuse when using an external authentication source like LDAP. Note that they won’t receive any error message since this would expose their account’s existence but no mail will be sent either.

Default URL: /password_reset/

Optional arguments:

template_name: The full name of a template to use for displaying the password reset form. Defaults toregistration/password_reset_form.htmlif not supplied.email_template_name: The full name of a template to use for generating the email with the reset password link. Defaults toregistration/password_reset_email.htmlif not supplied.subject_template_name: The full name of a template to use for the subject of the email with the reset password link. Defaults toregistration/password_reset_subject.txtif not supplied.password_reset_form: Form that will be used to get the email of the user to reset the password for. Defaults toPasswordResetForm.token_generator: Instance of the class to check the one time link. This will default todefault_token_generator, it’s an instance ofdjango.contrib.auth.tokens.PasswordResetTokenGenerator.post_reset_redirect: The URL to redirect to after a successful password reset request.from_email: A valid email address. By default Django uses theDEFAULT_FROM_EMAIL.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.html_email_template_name: The full name of a template to use for generating atext/htmlmultipart email with the password reset link. By default, HTML email is not sent.

Template context:

form: The form (seepassword_reset_formabove) for resetting the user’s password.

Email template context:

email: An alias foruser.emailuser: The currentUser, according to theemailform field. Only active users are able to reset their passwords (User.is_active is True).site_name: An alias forsite.name. If you don’t have the site framework installed, this will be set to the value ofrequest.META["SERVER_NAME"].domain: An alias forsite.domain. If you don’t have the site framework installed, this will be set to the value ofrequest.get_host().protocol: http or httpsuid: The user’s primary key encoded in base 64.token: Token to check that the reset link is valid.

Sample registration/password_reset_email.html (email body template):

Someone asked for password reset for email {{ email }}. Follow the link below:

{{ protocol}}://{{ domain }}{% url "password_reset_confirm" uidb64=uid token=token %}

The same template context is used for subject template. Subject must be single line plain text string.

password_reset_done

django.contrib.auth.views.password_reset_done(request[, *template_name*, *current_app*, *extra_context*])

The page shown after a user has been emailed a link to reset their password. This view is called by default if the password_reset() view doesn’t have an explicit post_reset_redirect URL set.

Default URL: /password_reset_done/

Note

If the email address provided does not exist in the system, the user is inactive, or has an unusable password, the user will still be redirected to this view but no email will be sent.

Optional arguments:

template_name: The full name of a template to use. Defaults toregistration/password_reset_done.htmlif not supplied.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

password_reset_confirm

django.contrib.auth.views.password_reset_confirm(request[, *uidb64*, *token*, *template_name*,*token_generator*, *set_password_form*, *post_reset_redirect*, *current_app*, *extra_context*])

Presents a form for entering a new password.

Default URL: /password_reset_confirm/

Optional arguments:

uidb64: The user’s id encoded in base 64. Defaults toNone.token: Token to check that the password is valid. Defaults toNone.template_name: The full name of a template to display the confirm password view. Default value isregistration/password_reset_confirm.html.token_generator: Instance of the class to check the password. This will default todefault_token_generator, it’s an instance ofdjango.contrib.auth.tokens.PasswordResetTokenGenerator.set_password_form: Form that will be used to set the password. Defaults toSetPasswordFormpost_reset_redirect: URL to redirect after the password reset done. Defaults toNone.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

Template context:

form: The form (seeset_password_formabove) for setting the new user’s password.validlink: Boolean, True if the link (combination ofuidb64andtoken) is valid or unused yet.

password_reset_complete

django.contrib.auth.views.password_reset_complete(request[, *template_name*, *current_app*,*extra_context*])

Presents a view which informs the user that the password has been successfully changed.

Default URL: /password_reset_complete/

Optional arguments:

template_name: The full name of a template to display the view. Defaults toregistration/password_reset_complete.html.current_app: A hint indicating which application contains the current view. See the namespaced URL resolution strategy for more information.extra_context: A dictionary of context data that will be added to the default context data passed to the template.

The redirect_to_login helper function

django.contrib.auth.views.redirect_to_login(next[, *login_url*, *redirect_field_name*])

Django provides a convenient function, redirect_to_login that can be used in a view for implementing custom access control. It redirects to the login page, and then back to another URL after a successful login.

Required arguments:

next: The URL to redirect to after a successful login.

Optional arguments:

login_url: The URL of the login page to redirect to. Defaults toLOGIN_URLif not supplied.redirect_field_name: The name of aGETfield containing the URL to redirect to after log out. Overridesnextif the givenGETparameter is passed.

Built-in forms

If you don’t want to use the built-in views, but want the convenience of not having to write forms for this functionality, the authentication system provides several built-in forms located indjango.contrib.auth.forms:

Note

The built-in authentication forms make certain assumptions about the user model that they are working with. If you’re using a custom User model , it may be necessary to define your own forms for the authentication system.

AdminPasswordChangeForm

A form used in the admin interface to change a user’s password.

Takes the user as the first positional argument.

AuthenticationForm

A form for logging a user in.

Takes request as its first positional argument, which is stored on the form instance for use by sub-classes.

django.contrib.auth.views.confirm_login_allowed(user)

By default, AuthenticationForm rejects users whose is_active flag is set to False. You may override this behavior with a custom policy to determine which users can log in. Do this with a custom form that subclasses AuthenticationForm and overrides the confirm_login_allowed method. This method should raise aValidationError if the given user may not log in.

For example, to allow all users to log in, regardless of “active” status:

from django.contrib.auth.forms import AuthenticationForm

class AuthenticationFormWithInactiveUsersOkay(AuthenticationForm):

def confirm_login_allowed(self, user):

pass

Or to allow only some active users to log in:

class PickyAuthenticationForm(AuthenticationForm):

def confirm_login_allowed(self, user):

if not user.is_active:

raise forms.ValidationError(

_("This account is inactive."),

code="inactive",

)

if user.username.startswith("b"):

raise forms.ValidationError(

_("Sorry, accounts starting with "b" aren"t welcome here."),

code="no_b_users",

)

PasswordChangeForm

A form for allowing a user to change their password.

PasswordResetForm

A form for generating and emailing a one-time use link to reset a user’s password.

django.contrib.auth.views.send_email(subject_template_name, email_template_name, context, from_email,to_email[, *html_email_template_name=None*])

Uses the arguments to send an EmailMultiAlternatives. Can be overridden to customize how the email is sent to the user.

subject_template_name: the template for the subject.

email_template_name: the template for the email body.

context: context passed to the

subject_template,email_template,

and `html_email_template` (if it is not `None`).

from_email: the sender’s email.

to_email: the email of the requester.

html_email_template_name: the template for the HTML body;

defaults to `None`, in which case a plain text email is sent.

By default, save() populates the context with the same variables that password_reset() passes to its email context.

SetPasswordForm

A form that lets a user change their password without entering the old password.

UserChangeForm

A form used in the admin interface to change a user’s information and permissions.

UserCreationForm

A form for creating a new user.

Authentication data in templates

The currently logged-in user and their permissions are made available in the template context when you use RequestContext.

USERS

When rendering a template RequestContext, the currently logged-in user, either a User instance or anAnonymousUser instance, is stored in the template variable {{ user }}:

{% if user.is_authenticated %}

<p>Welcome, {{ user.username }}. Thanks for logging in.</p>

{% else %}

<p>Welcome, new user. Please log in.</p>

{% endif %}

This template context variable is not available if a RequestContext is not being used.

PERMISSIONS

The currently logged-in user’s permissions are stored in the template variable {{ perms }}. This is an instance of django.contrib.auth.context_processors.PermWrapper, which is a template-friendly proxy of permissions.

In the {{ perms }} object, single-attribute lookup is a proxy to User.has_module_perms. This example would display True if the logged-in user had any permissions in the foo app:

{{ perms.foo }}

Two-level-attribute lookup is a proxy to User.has_perm. This example would display True if the logged-in user had the permission foo.can_vote:

{{ perms.foo.can_vote }}

Thus, you can check permissions in template {% if %} statements:

{% if perms.foo %}

<p>You have permission to do something in the foo app.</p>

{% if perms.foo.can_vote %}

<p>You can vote!</p>

{% endif %}

{% if perms.foo.can_drive %}

<p>You can drive!</p>

{% endif %}

{% else %}

<p>You don"t have permission to do anything in the foo app.</p>

{% endif %}

It is possible to also look permissions up by {% if in %} statements. For example:

{% if "foo" in perms %}

{% if "foo.can_vote" in perms %}

<p>In lookup works, too.</p>

{% endif %}

{% endif %}

Managing users in the admin

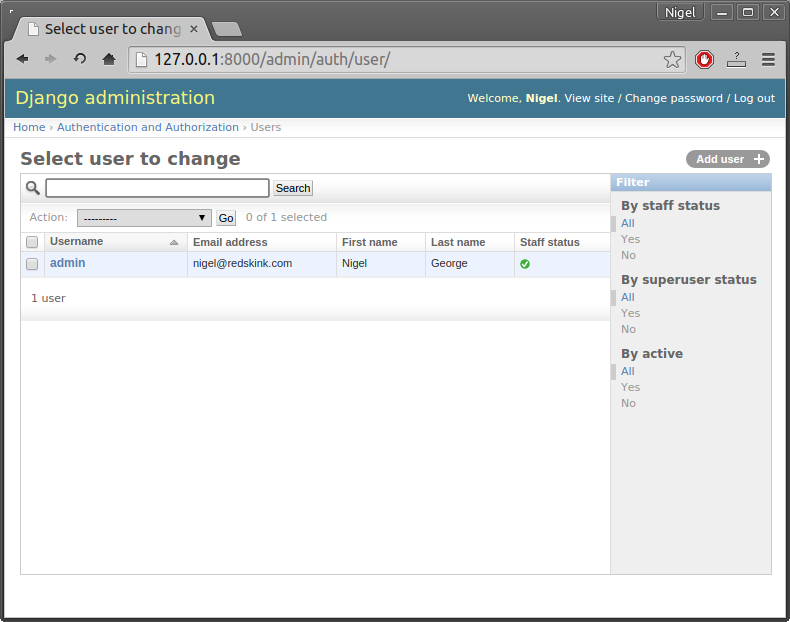

When you have both django.contrib.admin and django.contrib.auth installed, the admin provides a convenient way to view and manage users, groups, and permissions. Users can be created and deleted like any Django model. Groups can be created, and permissions can be assigned to users or groups. A log of user edits to models made within the admin is also stored and displayed.

Creating Users

You should see a link to “Users” in the “Auth” section of the main admin index page.

Figure 11-1: Django admin user management screen

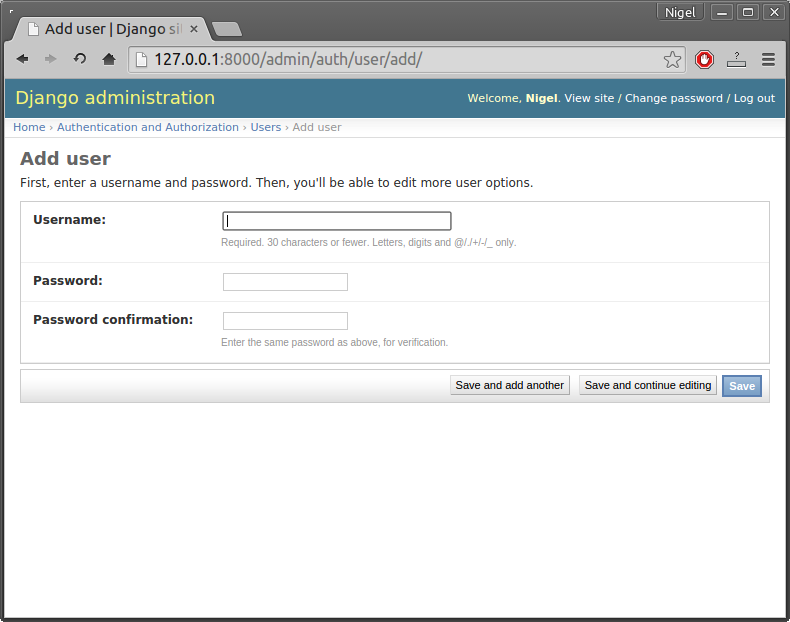

The “Add user” admin page is different than standard admin pages in that it requires you to choose a username and password before allowing you to edit the rest of the user’s fields.

Figure 11-2: Django admin add user screen

Also note: if you want a user account to be able to create users using the Django admin site, you’ll need to give them permission to add users and change users (i.e., the “Add user” and “Change user” permissions). If an account has permission to add users but not to change them, that account won’t be able to add users. Why? Because if you have permission to add users, you have the power to create superusers, which can then, in turn, change other users. So Django requires add and change permissions as a slight security measure.

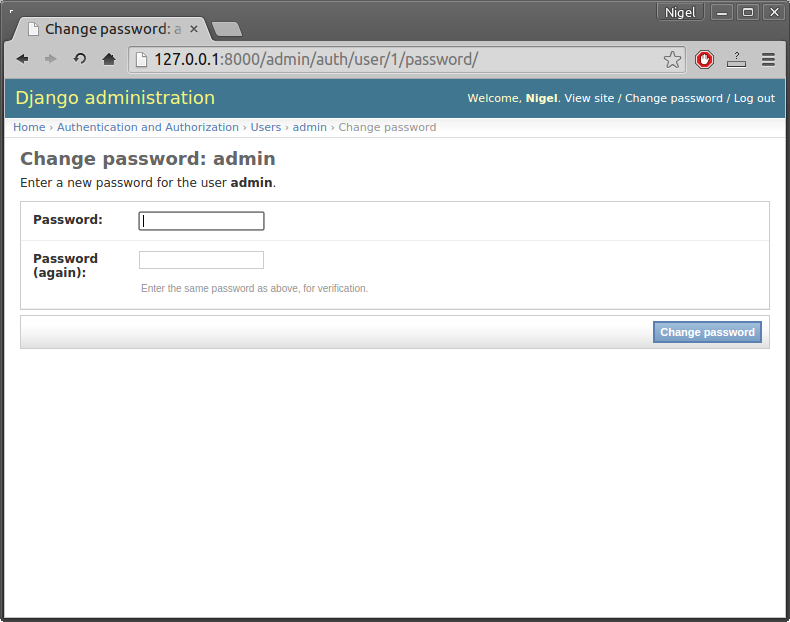

Changing Passwords

User passwords are not displayed in the admin (nor stored in the database), but the password storage details are displayed. Included in the display of this information is a link to a password change form that allows admins to change user passwords.

Figure 11-3: Link to change password (circled)

Figure 11-4: Django admin change password form

Password management in Django

Password management is something that should generally not be reinvented unnecessarily, and Django endeavors to provide a secure and flexible set of tools for managing user passwords. This document describes how Django stores passwords, how the storage hashing can be configured, and some utilities to work with hashed passwords.

How Django stores passwords

Django provides a flexible password storage system and uses PBKDF2 by default.

The password attribute of a User object is a string in this format:

<algorithm>$<iterations>$<salt>$<hash>

Those are the components used for storing a User’s password, separated by the dollar-sign character and consist of: the hashing algorithm, the number of algorithm iterations (work factor), the random salt, and the resulting password hash. The algorithm is one of a number of one-way hashing or password storage algorithms Django can use; see below. Iterations describe the number of times the algorithm is run over the hash. Salt is the random seed used and the hash is the result of the one-way function.

By default, Django uses the PBKDF2 algorithm with a SHA256 hash, a password stretching mechanism recommended by NIST. This should be sufficient for most users: it’s quite secure, requiring massive amounts of computing time to break.

However, depending on your requirements, you may choose a different algorithm, or even use a custom algorithm to match your specific security situation. Again, most users shouldn’t need to do this – if you’re not sure, you probably don’t. If you do, please read on:

Django chooses the algorithm to use by consulting the PASSWORD_HASHERS setting. This is a list of hashing algorithm classes that this Django installation supports. The first entry in this list (that is,settings.PASSWORD_HASHERS[0]) will be used to store passwords, and all the other entries are valid hashers that can be used to check existing passwords. This means that if you want to use a different algorithm, you’ll need to modify PASSWORD_HASHERS to list your preferred algorithm first in the list.

The default for PASSWORD_HASHERS is:

PASSWORD_HASHERS = [

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2PasswordHasher",

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2SHA1PasswordHasher",

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.BCryptSHA256PasswordHasher",

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.BCryptPasswordHasher",

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.SHA1PasswordHasher",

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.MD5PasswordHasher",

"django.contrib.auth.hashers.CryptPasswordHasher",

]

This means that Django will use PBKDF2 to store all passwords, but will support checking passwords stored with PBKDF2SHA1, bcrypt, SHA1, etc. The next few sections describe a couple of common ways advanced users may want to modify this setting.

Using bcrypt with Django

Bcrypt is a popular password storage algorithm that’s specifically designed for long-term password storage. It’s not the default used by Django since it requires the use of third-party libraries, but since many people may want to use it Django supports bcrypt with minimal effort.

To use Bcrypt as your default storage algorithm, do the following:

Install the bcrypt library. This can be done by running

pip install django[bcrypt], or by downloading the library and installing it withpython setup.py install.Modify

PASSWORD_HASHERSto listBCryptSHA256PasswordHasherfirst. That is, in your settings file, you’d put:PASSWORD_HASHERS = [ "django.contrib.auth.hashers.BCryptSHA256PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.BCryptPasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2SHA1PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.SHA1PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.MD5PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.CryptPasswordHasher", ](You need to keep the other entries in this list, or else Django won’t be able to upgrade passwords; see below).

That’s it – now your Django install will use bcrypt as the default storage algorithm.

Password truncation with BCryptPasswordHasher

The designers of bcrypt truncate all passwords at 72 characters which means thatbcrypt(password_with_100_chars) == bcrypt(password_with_100_chars[:72]). The original BCryptPasswordHasherdoes not have any special handling and thus is also subject to this hidden password length limit.BCryptSHA256PasswordHasher fixes this by first first hashing the password using sha256. This prevents the password truncation and so should be preferred over the BCryptPasswordHasher. The practical ramification of this truncation is pretty marginal as the average user does not have a password greater than 72 characters in length and even being truncated at 72 the compute powered required to brute force bcrypt in any useful amount of time is still astronomical. Nonetheless, we recommend you use BCryptSHA256PasswordHasheranyway on the principle of “better safe than sorry”.

Other bcrypt implementations

There are several other implementations that allow bcrypt to be used with Django. Django’s bcrypt support is NOT directly compatible with these. To upgrade, you will need to modify the hashes in your database to be in the form bcrypt$(raw bcrypt output). For example:bcrypt$$2a$12$NT0I31Sa7ihGEWpka9ASYrEFkhuTNeBQ2xfZskIiiJeyFXhRgS.Sy.

Increasing the work factor

The PBKDF2 and bcrypt algorithms use a number of iterations or rounds of hashing. This deliberately slows down attackers, making attacks against hashed passwords harder. However, as computing power increases, the number of iterations needs to be increased. We’ve chosen a reasonable default (and will increase it with each release of Django), but you may wish to tune it up or down, depending on your security needs and available processing power. To do so, you’ll subclass the appropriate algorithm and override the iterations parameters. For example, to increase the number of iterations used by the default PBKDF2 algorithm:

Create a subclass of

django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2PasswordHasher:from django.contrib.auth.hashers import PBKDF2PasswordHasher class MyPBKDF2PasswordHasher(PBKDF2PasswordHasher): """ A subclass of PBKDF2PasswordHasher that uses 100 times more iterations. """ iterations = PBKDF2PasswordHasher.iterations * 100Save this somewhere in your project. For example, you might put this in a file like

myproject/hashers.py.Add your new hasher as the first entry in

PASSWORD_HASHERS:PASSWORD_HASHERS = [ "myproject.hashers.MyPBKDF2PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.PBKDF2SHA1PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.BCryptSHA256PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.BCryptPasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.SHA1PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.MD5PasswordHasher", "django.contrib.auth.hashers.CryptPasswordHasher", ]

That’s it – now your Django install will use more iterations when it stores passwords using PBKDF2.

Password upgrading

When users log in, if their passwords are stored with anything other than the preferred algorithm, Django wil

- 文章导航